Heritage Research Kitchen at Kenwood House, London

On Saturday 12 November, Historic England and English Heritage research staff and doctoral students from partner universities took part in the 2022 Being Human Festival. Members of the public joined us in The Old Kitchen at Kenwood House for a family-friendly ‘drop-in’ event. Visitors met with our researchers to learn about the methods we use to make new knowledge ‘breakthroughs’, and how these inform our work to protect, interpret, and help people enjoy the historic environment. Here you can find audio recordings and transcripts of talks from the event.

- About the event

- 'What Can Graffiti Tell us About People in the Past and Present?', by Emma Bryning

- 'A Window onto the Medieval World', by Bronwen Stone

- 'Reclaim your Historic High Street', by Alfie Lien-Talks

- 'Visualising Loss: How interactive documentaries can be used to understand and communicate heritage loss on the coast', by Tanya Venture

- 'English Synagogues and Jewish Heritage', by Jessie Clark

- 'Old Bones: Using Neutron and X-ray Tomography to Look Inside Archaeological Bones', by Chloe Pearce

- Contact

About the event

We produced a banner exhibition, with interactive, family friendly table-top activities, where visitors could ask questions and share their thoughts on research spanning the English medieval glass industry to graffiti at heritage sites and managing coastal change.

Our researchers also held a series of 5 minute "Lightning Talks", giving insights into their work and how it can help us appreciate different aspects of the historic environment around us. You can listen to these talks via the links below.

This event was part of the Being Human Festival of the Humanities 2022, led by the University of London, with the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and The British Academy.

'What Can Graffiti Tell us About People in the Past and Present?', by Emma Bryning

Read the transcription of 'What Can Graffiti Tell us About People in the Past and Present?'

My name is Emma Bryning and I am working on a project with English Heritage and the University of York looking at historic and contemporary graffiti and considering whether understanding graffiti creation today can help us to better understand historic mark-making in the past. Today I am going to be discussing: What can Graffiti Tell us About People in the Past?

It is important to know that until the 19th century the practice of graffiti was largely tolerated, and it was only later that it became viewed as a form of vandalism. It is now considered a heritage crime to leave graffiti at historic sites. Historic graffiti can be found at most English Heritage sites and these marks can help to reveal further information about how people have interacted with these places, whilst also showing how attitudes to graffiti have changed over time.

Graffiti from the Second World War has been found at both Belsay Hall - left by soldiers who were stationed there - and at Audley End, by Polish special forces who were training at the site. Meanwhile, at Portchester Castle, a variety of graffiti can be found across the site left by French prisoners of war during the Napoleonic Wars.

I am now going to look at two more in-depth case studies of graffiti at English Heritage sites:

Richmond Castle, in North Yorkshire, is one of the great Norman fortresses in England. By the 16th-century it had become derelict and later in the late 18th and early 19th century, the castle became a fashionable place for tourists to visit and also inspired artistic works including paintings by JMW Turner. During the Victorian period, Richmond castle was leased out by the Duke of Richmond to the North York Militia and in 1908 it became the headquarters of the Northern Territorial Army.

During the First World War, Richmond Castle was used by the northern Non-Combatant Corps, men who were exempt from military service but who contributed to the war effort through non-combatant roles. However, some of the men refused to contribute to the war effort in any way due to their religious, social or political beliefs. Due to this refusal, these conscientious objectors were detained in the cell blocks at Richmond Castle, and many left evidence of their experiences by writing and drawing on the walls of the cells.

Through a recent graffiti recording project, funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, over 2000 graffiti were found, including marks left by the conscientious objectors detained in the cells. In 1916, Richard Lewis Barry wrote on one of the cells: ‘You might just as well try to dry a floor by throwing water on it, as to try to end this war by fighting.’ The conscientious objectors detained in the cell blocks knew that they could eventually face being court martialled due to their refusal to obey orders. In the face of such an uncertain future, leaving graffiti to mark their existence or record their personal views and experiences likely took on great significance.

Kirby Hall was one of the great Elizabethan houses of England. It was founded by Sir Humphrey Stafford in the 1570s, but was later abandoned and left to fall into ruin by the Finch-Hattons in the late 18th-century. Later, during the 19th-century, it became a popular historic attraction. A recent graffiti recording survey has found over 2000 marks across the site, including dated graffiti ranging from 1757 to 2021. Such marks help to provide more information about the site’s history as well as providing a further insight into how people have interacted with Kirby Hall - and subsequently left their mark - over time.

Hundreds of graffiti have been found in the attic rooms at Kirby Hall, with many of these marks dating to the 1880s. During this period of time, groups and individuals visiting the site on unofficial tours seem to have made their way up to the attic, there leaving their mark and record of their time spent at Kirby Hall. However, in the 1890s, the agent of Murray Edward Gordon Finch-Hatton, the 12th Earl of Winchilsea and 7th Earl of Nottingham, displayed a poster at Kirby Hall warning visitors that it was an offence to deface or leave their names on the walls of the building. It was also in the 1890s that the Earl began running official tours of Kirby Hall and his nearby Weldon Quarry. The lack of graffiti in the attic from the 1890s subsequently reflects the changing usage of the site.

It was also around this time that William Bennett and Lacy Colbert Richards, of the nearby town of Oundle, marked their names into one of the columns in the Loggia on 17th August 1880. William, a then 20-year-old Painter Journeyman, was still living in Oundle, whilst Lacy, a tailor, was working in Nuneaton. The graffiti they left behind now serves as a record of these two local lads being reunited and their visit to Kirby Hall over 140 years ago.

'A Window onto the Medieval World', by Bronwen Stone

Read the transcription of 'A window on the Medieval World'

My name is Bronwen Stone. I’m a PhD research student at the University of Sheffield working in collaboration with Historic England, researching the origins and use of early English glass in glazing.

In the medieval period, window glass was incredibly rare and only used in high status buildings such as churches, monasteries, palaces and halls. In the Anglo-Norman period it was imported from the continent - northern France and Germany for example, but there is evidence, albeit sparse, that an industry developed in this country sometime in the 13th century.

My research will add to this evidence through a study of excavated 13th – 15th century window glass from selected sites. My focus is on Benedictine and Cistercian monasteries and includes assemblages from Rievaulx and Whitby in the north, Alcester, Louth and Bordesley in the midlands and the east of the country, and Hyde in the south.

The window glasses come from dissolution layers – that is material dumped during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. In the case of the windows, while some were sold or moved on to local churches for example, others were stripped of their lead, which was melted down and reused, and the glass simply thrown away. This is the glass that I’m interested in.

The problem, however, is that excavated window glass is often very small and highly corroded, which makes identifying diagnostic features difficult – although not impossible. There is also a bias in the archaeological record: we don’t know exactly what has been dumped, and we can never be sure what proportion of the window we have retrieved. But the small excavated fragments fit easily into the laboratory instrument that I use on the project - such as a micro XRF that measures the chemical composition - so important information can be gathered from material culture that has up until recently, been overlooked.

How will I use these excavated fragments to illuminate the fledgling industry in medieval England?

I will create a profile of the glasses from each site through a stylistic, technical and chemical analysis. Stylistic analysis allows me to date the glasses based on their applied decoration, an example of which is stiff leaf grisaille that was popular in the early-mid 13th century, or the Black Gothic lettering seen on windows from around the 14th century. A technical analysis involves examining the fragments for evidence of how it was made; a characteristic fire rounded edge for one type of production called cylinder method, or an undulating surface for the crown production. Having selected representative samples based on the first two analyses, I will use X-rays to determine chemical composition. This will tell me about the raw materials that were used, and the recipe that was followed. I will get an idea of how these changed geographically and over time, and perhaps provenance the glasses to known production sites such as The Weald in the south, Staffordshire or on the continent.

Through a study of window glass over time and over space, I aiming to understand how the industry developed in this country. The 13th to 15th centuries were times of dramatic social, economic and political change. So it will be interesting to see how factors such as agricultural improvements, fluctuations in the population, wars and of course, the Black Death affected supply and use. In addition, there are geographical considerations: transport networks and trade routes to the new monastic sites that had been created in the wave of building since the time of the Norman Conquest.

This was an industry that was highly skilled and organised - so how responsible were immigrant workers for stimulating the industry and can we see signs of experienced production in the excavated glass fragments used in the study?

Not many people have looked at excavated fragments, so to have the chance to study previously un-researched and published material is very exciting. The monastic orders I am looking at have a contrasting approach to living and worship, so it will be fascinating to identify whether differences carry over into the use of window glass.

'Reclaim your Historic High Street', by Alfie Lien-Talks

Read the transcription of 'Reclaim your Historic High Street'

Hello, have you been to the High Street in the last year? How about 6 months? We all know that the High Street is an important part of Britain’s character, yet it is struggling. The good news is that you and I can work together to ensure its longevity for the future.

My name is Alfie Lien-Talks, and I am a current PhD student at the University of York, working alongside Historic England and the Archaeology Data Service. Today I am here to talk about my research all about Reclaiming the Historic High Street.

Why the Historic High Street?

I’m sure that we all have our own stories associated with the Historic High Street. For me, it is as a child going to the local bakers to get a giant chocolate chip cookie. For you it may be having a significant meeting with a friend or learning about a local development.

The High Street has long been associated with the idea of shopping, but also wider social interactions as the centre of the community. The beginnings of today’s recognisable High Street coincided with the movement of people into more urban areas, and High Streets provided opportunities to shop, meet and share ideas. The High Street started in earnest with the medieval markets. In the 16th century, these were augmented with shopping galleries (such as the Royal Exchange), then 19th- century bazaars, Victorian Cooperative stores and the Great Exhibition of 1851. In the 20th century shopping centres were developed, sometimes in urban centres and sometimes away from the traditional High Street.

But High Streets have not just been about shopping. As mentioned they were the place to get, share and develop ideas. For instance, Stock Exchanges started in coffee shops. They have also been the centre of many rights movements, such as workers’ rights and the Suffragettes. As a result of their rich history, High Streets contain much information about the lives of individuals throughout these periods. And crucially for today, we can learn from these different aspects of history to inform how we might be able to turn them back into centres for the community.

As I am sure you all know, the recent Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated a recent decline in the traditional High Street. The lockdowns have made us less reliant on these physical community spaces, and many would rather get their items online.

The concept of the ‘dying High Street’ is an emotionally loaded term and is associated with struggling shops. However, as mentioned, High Streets are not just about shopping and many began their popularity as places to congregate. Historic England are working on 67 High Streets with local communities and interested parties to help encourage economic, social and cultural recovery.

As a result, Historic England is looking into how to make the High Street back into a community space. To do this, a range of research projects are being carried out. These include looking at historical photographs, archaeological investigations, historic building analysis, recording local stories and 3D modelling. In my PhD, I research how to make this information available to the public as well as to professional researchers.

So, what do I actually do in my research? I work with local research groups and organisations to try and ensure that all the information on the High Street is gathered, stored and used as effectively as possible. Within this, there is a lot of complexity. Firstly, the types of research are very different. The Historic High Street is such a complicated historical landscape, there is building, archaeological and archival evidence, photographs, and a lot of cultural history as well. Secondly, there are many ways of storing this information for the long term. Thirdly, digital methods can provide flexible, quick and easy access to this information. This is where my research comes in. By combining these three factors, I am trying to ensure that all the information from the Historic High Street has the maximum potential to be used to help the High Street.

The Historic High Street is not just about the stories from the past, it’s about how these can affect the future.

So, if the High Street is important to you, please email me your thoughts on its future. Your High Street needs you!

Have you ever tried searching for information about your local High Street, maybe researching your ancestors or your local area? What was it like looking for that information, where did you go and what would you like to know?

Or alternatively, do you have your own story of the High Street? Come and share your stories about what has made the British High Street great, and let’s reclaim it for the community.

If you want to get more involved contact me at [email protected] and I would love to have your opinions.

'Visualising Loss: How interactive documentaries can be used to understand and communicate heritage loss on the coast', by Tanya Venture

Read the transcription of 'Visualising Loss'

My name is Tanya Venture and I am a collaborative doctoral partnership PhD student with the University of Exeter and Historic England, working on a project about understanding and communicating heritage loss on the coast using interactive documentaries.

From footprints in the foreshore to imposing castles and grand promenades, the history of the coast is written in the places left behind. These places are not just relics of a bygone era, they are important places to us today. These are the places that we visit on holiday, the places that we might live by or the places where we work. It might be tempting to think of these places as timeless or unchanging, but places do change, especially those on the coast. The coast is a dynamic area, always changing though natural coastal processes. However, these can lead to radical changes and in some cases inevitable loss of some of these beloved places. This will only become more prevalent with the increasing effects of climate change, which will affect all types of heritage both inland and coastal – from built to buried.

Loss isn’t always a bad thing. It has led to amazing discoveries, created new opportunities for engagement with the past and may also create value through highlighting our own current relationships with place now. However, at its heart loss is a difficult and emotional thing and this is especially true when managing sites that will be facing inevitable future change. The first step to managing these types of sites is being able and confident in starting the conversation about what loss means to these sites and more importantly the people who care for them. This is where my project comes in.

My work aims to firstly articulate what loss actually means to heritage sites and then help people visualise what this loss means to the sites around them. I started by breaking down what loss physically means to heritage sites into four themes; invisible, inevitable, adaptive and radical. This formed the basis for the next step of my project – to create a platform where conversations around loss can be discussed and reflected upon between both heritage professionals and the wider public.

To do this I’ve chosen to create an Interactive documentary or i-doc. An i-doc is a non-fiction documentary style narrative with interactivity at the heart of its structure. Kind of like a ‘chose your own adventure’ novel where the story moves along based on your choices. The interactive elements invite you to move from being the passive audience watching the content, to the more active position of assistant director helping to create that content’s narrative. It is this interactivity that I think will help challenge preconceived notions of what loss means and really get the audience to interrogate for themselves what loss means to them personally and to heritage assets.

The interactive documentary that I’ve created as part of this PhD work features over a 1000 individual clips from 39 participants talking about four different case study sites around the south-west, all undergoing some form of loss or radical change. You can find and engage with the i-doc Visualising Loss now at www.visualisingloss.co.uk where you can work your way through the collection of conversations fragments presented. There is also an optional questionnaire that you can complete and win one of three amazon vouchers. I would be really interested in hearing about your thoughts on what visualising loss means to you.

'English Synagogues and Jewish Heritage', by Jessie Clark

Read the transcript of 'English Synagogues and Jewish Heritage'

My name is Jessie Clark. I am a PhD student at the University of Bath and working with Historic England researching the representation of Jewish heritage and identity in modern English synagogue buildings.

The Jewish community is extremely diverse. There are Jewish communities across the globe and many of these traditions can be seen across England today. Whilst the majority of English Jews have ancestry from Eastern and Central Europe, falling into a tradition called Ashkenazi Judaism, the oldest Jewish community in England has ancestors from Spain and Portugal and follows a tradition known as Sephardi Judaism. All of the many different Jewish traditions practice Judaism with different customs and cultures. These differences can affect the ways in which congregations choose to build and lay out their synagogue buildings.

Whilst synagogues are known as the Jewish place of worship, they are not inherently sacred buildings. Jewish prayer can take place anywhere and many important religious activities take place outside the synagogue, especially in people’s homes. It is the rituals and actions of people and a community which makes any space sacred within Judaism. Indeed, in Hebrew, the synagogue has three names: Beit HaKnesset – house of meeting – Beit HaMidrash – house of learning - and Beit Ha Tefillah – house of prayer. These three different names reflect the multifunctionality of the synagogue.

This also means that there are no specific religious regulations that need to be followed when building a synagogue. However, unsurprisingly, over the centuries, traditions have arisen when congregations build a synagogue.

In western Europe, including England, the ark where the Torah scrolls are kept is usually situated on the eastern wall, pointing towards Jerusalem. This is because it is customary to face towards Jerusalem to say certain prayers during a service. Most synagogues will have a bimah or raised platform from which the service leader will say prayers and the Torah is read. The Ner Tamid, or everlasting light – which is a symbol of the all-encompassing presence of God - is also common. The majority of synagogues in England have separate spaces for men and women to pray. Some congregations have a ladies’ gallery above the sanctuary, whilst others divide the sanctuary in two.

However, synagogues do have differences depending not just on the circumstances of the congregation but also on cultures and beliefs of the community they serve. Men and women praying separately is perhaps the most obvious, as in some congregations men and women sit together during services. Other aspects of the synagogue reflect different traditions, for example where the bimah is found in the sanctuary changes depending on the cultural ancestry of a congregation.

My research is considering how these, and other aspects of the synagogue building can be interpreted as expressions of Jewish heritage as well as Jewish religion. Heritage research has shown that in any society, what we value and choose to show as our history reflects our priorities and identity as a community. Therefore, by considering how different Jewish communities portray their Jewish heritage, this could help broaden knowledge on the values and identities of Jewish congregations.

I am visiting several communities to compare how these expressions differ across the country and to consider how Jewish heritage can be better understood and how heritage organisations can best work with Jewish communities to conserve, preserve and manage built Jewish heritage. I am considering if and how these reflect the different aspects that make up Jewish heritage: global Jewish history, English Jewish history and the history and experiences of the specific congregation.

To bring it back to synagogues in England, for example, the earliest Jewish communities were not allowed to build synagogues on main roads. Their places of worship were therefore set back and externally quite plain. When Jewish communities gained emancipation in the nineteenth century, researchers, especially the prominent historian Sharman Kadish, have argued that many congregations chose to express a very specific Anglo Jewish identity by building larger, grander synagogues. However, other communities wanted to keep synagogues smaller and worship in buildings similar to those found in Eastern Europe, thereby refuting what they saw as assimilation.

My research is considering if synagogues today can be analysed in the same way. It is hoping to continue to explore the role of synagogues for contemporary Jewish communities. Although they do not have inherent sacredness, it is clear from the congregations I have spoken to that they are incredibly important to them. Synagogues are a place where Jewishness can be explicitly expressed and the community can - as the Hebrew names reflect - meet, study and pray.

'Old Bones: Using Neutron and X-ray Tomography to Look Inside Archaeological Bones', by Chloe Pearce

Read the transcription of 'Old Bones'

My name is Chloe Pearce and I am a PhD student working with English Heritage and Birkbeck, University of London. Archaeological bone is an important resource. It can tell us lots about our past on both an individual and a settlement level – such as population distributions and patterns, and what people liked to eat. However, it is a material type at risk to environment deterioration in museum stores and display. This project is the first step in defining their ideal storage parameters.

Bone is a composite material, made up of both organic and mineral components that are intrinsically linked. They form a structure that gives bone its unique qualities – those qualities allow us to run, jump, climb and dance without hurting ourselves.

During burial bones undergo a degradation process called diagenesis. This is a complex process which breaks down the organic and mineral components – turning the bones to what we see today.

In my project I seek to better understand the preservation of the English Heritage archaeological bone collection, to support future research into improving the storage parameters of the collection. Many of the established methods to assess condition are invasive and destructive – requiring sampling which permanently alters the object. In conservation science we’re always looking for ways to limit the need for sampling, and we value those non-destructive options.

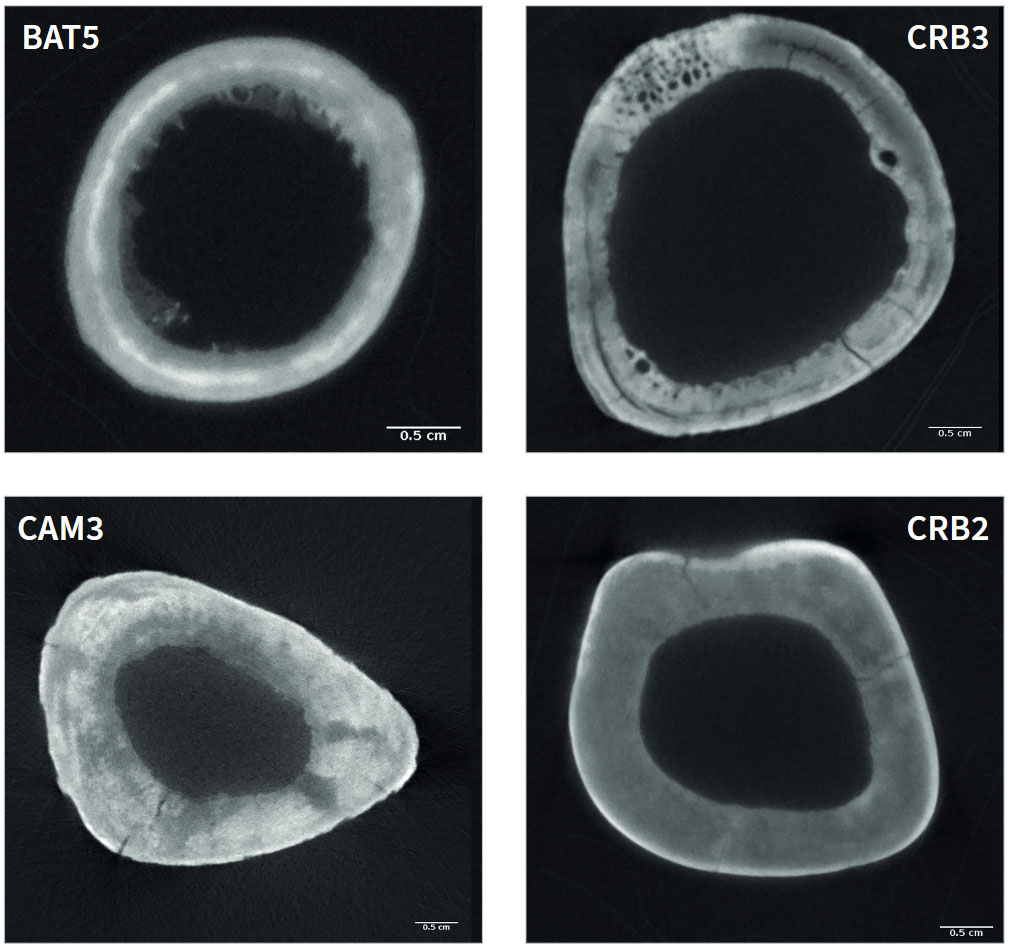

Neutron and X-ray tomography have provided a unique opportunity to assess the preservation of archaeological bone without changing the object. It uses a complicated process that turns hundreds of radiographs – much like what you have at the hospital after an injury – into hundreds of cross-section images. These images can be used to construct a 3D model. This allows us to see inside the bone. It is like being able to see tree rings without having to cut down the tree.

The two different radiation types complement each other and respond to the distinct components of bone.

Neutrons largely interact with light elements – such a hydrogen – and therefore interact with the bone’s organic material. During degradation original organic material is lost and new organic material enters the object. Therefore, after excavation we can expect different distributions of organics for different objects. For example, looking at the cross-sections of bones we might see a high concentration of organic material on the outer surface, telling us that these bones have gained lots of organic contamination.

Or bones may demonstrate lots of localised variation. Such bones can produce varied results if analysed using traditional techniques and knowing this could avoid costly analysis in the future that may not yield the results expected.

X-rays on the other hand provide us with information about the mineral component. These are of higher resolution than the neutron tomography. The information we can pull from this is about the structure of the object. For example, we can see additional or very small cracks in the X-ray tomography that we simply cannot see when we examine the bones by eye, revealing possible fragility and vulnerabilities. The method can reveal completely hidden damage, where, for example, beneath visible scarring on the bone is the surviving evidence of an impact, with small fractures and fragments. Being aware of such hidden structural detail is vital for highlighting the limitations of visual assessment and understanding that these areas may be more vulnerable to changes in their storage environment.

So, in conclusion, not only have these methods been non-invasive and left the object available for future analysis and display, we have also been privy to information that cannot be accessed any other way.

Research Kitchen Gallery

A selection of images from the event and of artefacts and historic places being studied.

Contact

For enquiries about this event please contact Adam Vamplew: [email protected]