Reinterpreting Contested Heritage

Owners or custodians of heritage that has become contested may be considering the need for action, and if so how to proceed. The case studies and links on this webpage are intended to support good practice and inform the process of research, consultation and reinterpretation.

Background to Historic England's work

England has a rich and complex history. Some of our buildings, monuments and places bring us face to face with parts of our history that conflict with today’s standards. We recognise that there are historic statues and sites which provoke strong and sometimes conflicting views.

We believe the best way to approach statues and sites which have become contested is not to remove them but to provide thoughtful, long-lasting and powerful reinterpretation, which keeps the structure’s physical context while adding new layers of meaning (also see our statement on contested heritage).

To demonstrate public engagement, creative commissioning and planning practice on contested heritage, Historic England commissioned British Future, an independent, non-partisan thinktank and registered charity, to compile a set of case studies from the UK and internationally. In addition to looking at examples where heritage has become contested, the case studies present reinterpretation (or interpretation) in places where stories have been hidden or not fully told.

The case studies are intended to complement government guidance on contested heritage.

List of reinterpretation case studies

-

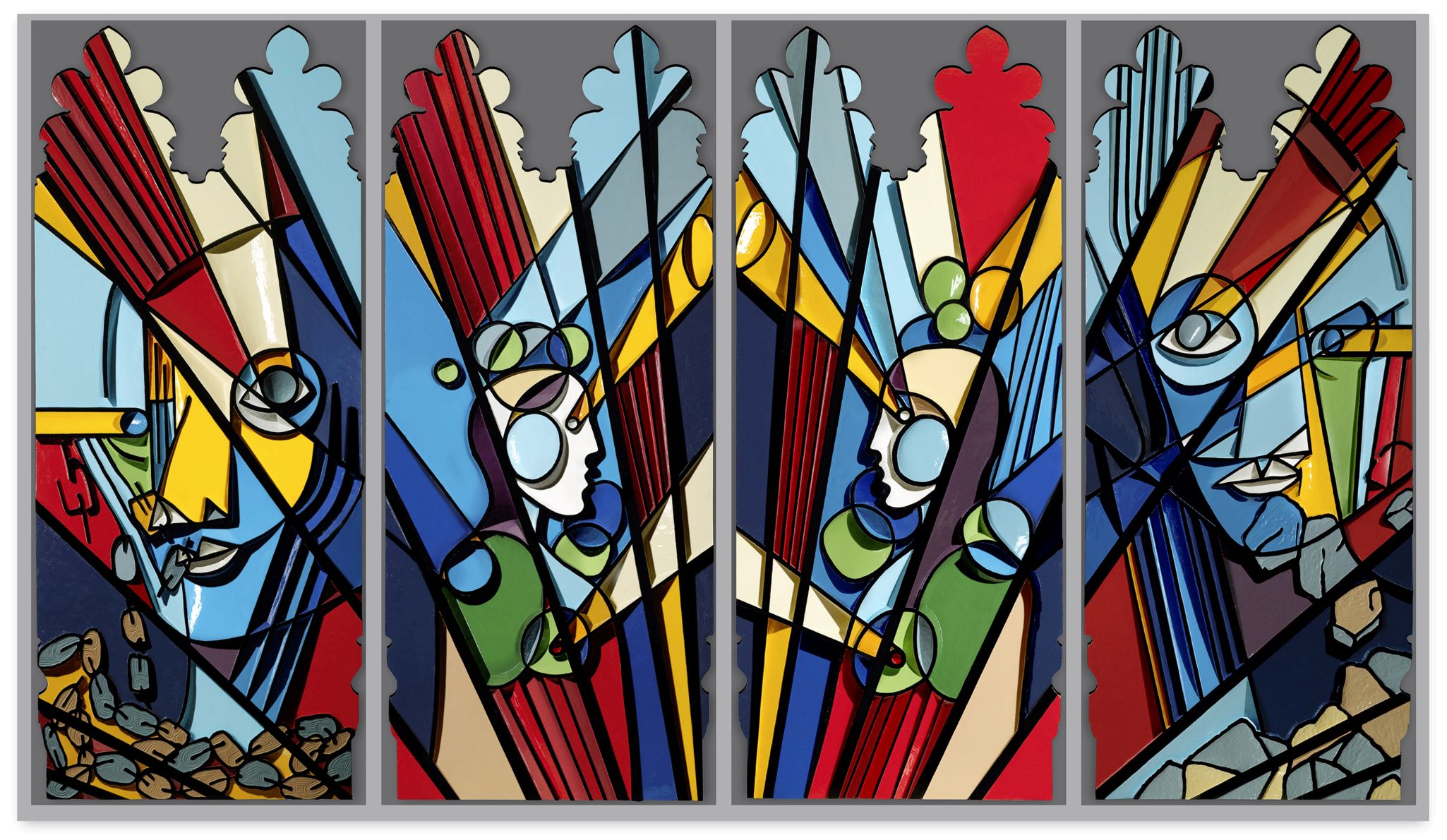

Case Study: Reconciliation Reredos – St Stephen’s Church, Bristol

A case study on reinterpreting heritage, featuring an artwork in a Bristol church that acknowledges the city's connections with transatlantic slavery.

-

Case Study: Liberty and Lottery Exhibition, Brodsworth Hall – Brodsworth, Doncaster

A case study on reinterpreting heritage, recognising a country house estate’s historical links with the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

-

Case Study: Edward Long Memorial, St Mary’s Church, Slindon, West Sussex

A case study on reinterpreting heritage, where a simple framed text document was installed to contextualise a memorial in a church.

-

Case Study: Commemorative Plaque – All Souls College Library, Oxford

A case study on reinterpreting heritage, featuring the installation of plaque commemorating enslaved people.

-

Case Study: Diamond War Memorial, Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland

A case study of reinterpreting heritage, featuring research and community engagement associated with a war memorial in Northern Ireland.

-

Case Study: the 'Coen Case', Westfries Museum, Hoorn, Netherlands

A case study on the reinterpretation of a contested statue of a Dutch historical figure and an engagement programme led by the nearby museum.

-

Case Study: 'Rumors of War' Sculpture – Richmond, Virginia, USA

A case study on reinterpreting heritage, from Virginia, USA, where a counter-memorial has been added to the local commemorative landscape.

-

Case Study: Millicent Fawcett Statue – Parliament Square, London

A case study on reinterpreting heritage, describing how a statue of a historic Women's Suffrage campaigner was installed at Parliament Square.

-

Case Study: Aballava Fort Contextual Plaque, St Michael’s Church, Burgh-by-Sands, Cumberland

A case study on reinterpreting heritage, featuring the installation of a plaque commemorating the first recorded African community in Britain.

-

Case Study: Confederate Monument – University of Mississippi (‘Ole Miss’), Oxford, Mississippi, USA

A case study on reinterpreting heritage from the USA, using a contextual plaque and the subsequent relocation of the monument within the same grounds.

Further reflections: learning from different approaches and common considerations

Together, the case studies exemplify how a wide array of approaches can be pursued when seeking to reinterpret heritage in a thoughtful, long-lasting and powerful way.

The cases are not presented as a simple guide to ‘best practice’. Each of the projects faced a range of distinct challenges. Those involved shared insights both from successful navigation of some of these challenges of reinterpretation, and reflections with hindsight on what was learned during the process of each project that could be of benefit to others starting on future projects.

It is beyond the scope of this case study resource to provide a comprehensive set of principles for conducting reinterpretation. However, thematic insights can be identified to assist others in developing thoughtful, long-lasting and powerful reinterpretation that can secure wide support.

Learning from different approaches

While reviewing the cases reveals some similarities in the responses to common challenges, the case studies also present important differences, showing how ‘retain and explain’ projects can be tailored to unique sites and contexts and may take on quite different forms and approaches.

Assessing potential approaches

Reinterpretation can be achieved in various ways, including counter-monuments, community engagement strategies, interactive exhibition spaces and education events. Strategies for reinterpretation can also provide moments for inclusivity that reveal histories not previously told, as well as responding to aspects of our heritage that are contested.

Any one or more of these options may be best suited to different contexts, and custodians of contested heritage sites should think carefully when assessing potential approaches. Some can be grounded in prompting discussion across divides, which may prove helpful to bringing people of different views together in more polarised contexts.

This was usefully demonstrated in the Reconciliation Reredos case at St Stephen’s Church in Bristol, which produced abstract artwork to open up conversations on Bristol’s past and convened community dialogue groups on contentious local issues.

Others may need to be primarily educative in their response, where there is less public knowledge on the complex history behind a heritage asset, or where custodians may be seeking to pre-empt and get in front of future potential contestation.

The ‘retain and explain’ approach centres the vital role played by tangible links to our past – in the form of statues, memorials and other commemorative works. These monuments, in part through their original purpose, are there to make us think and remember, and to ensure we do not forget about really important, even if really difficult, aspects of our history, and how we can learn from them to shape our future.

This point is well illustrated by the Edward Long memorial in St. Mary’s Church, Slindon, where few people knew about Long’s repugnant views and past influence. The memorial, accompanied by the interpretative text, can be the stimulus for reminding people of this.

Tailoring the approach to an asset and its context

The collated case studies draw attention to projects ranging from simple contextualisation documents, installed at low cost by volunteer-led grassroots organisations, through to high-profile counter-monuments and exhibitions led by professional organisations, which required substantial fundraising and the hiring of staff.

Some examples were able to install reinterpretation responses on the site of the heritage asset itself, following necessary consultation with planners and appropriate statutory advisory bodies. Others took approaches that could navigate more complex restrictions on listed or protected sites.

The Millicent Fawcett and Rumors of War statues, for instance, were both new interventions that consciously took a contextual approach to either redress the imbalance of pre-existing representation, or to directly provide a counterpoint monument to create a powerful response, and in both cases bring new levels of interpretation and context to protected statuary in their surrounding commemorative landscapes.

The Diamond War Memorial project alternatively focused on community engagement events and online and postal resources, which required few physical changes to the monument itself, except to make the existing monument more publicly accessible.

Different text-based approaches

In the case studies, we see different styles of the text-based reinterpretations. For example, at the Church of St Mary, Slindon, a fairly lengthy and dispassionate text conveys more information about the person memorialised, broadening the reader’s understanding of that person and encouraging reflection. This is framed in a simple and practical manner and hung below a monument in a church interior.

In contrast, at All Souls College, Oxford, a poetic text, resembling an invocation, is beautifully carved in stone and mounted in a semi open air space near the entrance to the library. Through its memorial focus on those enslaved on the plantations, it shifts the narrative away from the individual after whom the library had originally been named.

Reinterpretation should be conscious of the nature and context of the site but the approach cannot be prescriptive. A church monument tends to be economical with its words, but an effective response might consciously depart from this character. One should also consider how the user might engage with the monument or the place. Places of worship and libraries are contemplative spaces, with reflection and knowledge at their heart and a quiet atmosphere to encourage thought. A more public, open air and bustling place might encourage a different response. While not entirely public, the All Souls Library plaque shows the impact that a few well-chosen words can have on passers-by.

Common considerations

Reviewing the cases reveals differences between the approaches taken and some similarities in the responses to common challenges. This section focuses on the similarities, as a way to illuminate steps and processes relevant to the success of a broad range of reinterpretation projects.

Building a strong, evidenced basis for reinterpretation

It is an important foundation to be able to present a clear, objective and factual historical account that can communicate both what an asset represents and why it requires reinterpretation. Custodians of contested heritage assets should consult experts with detailed knowledge of the site and the relevant history, wherever possible, to help develop a research base which takes account of different historical interpretations. This should set out the origins of the site and its complex historical connections, which may include how relevant social attitudes on the asset or the narratives associated with it have changed over time.

Embedding structured consultation as an integral part of any reinterpretation process

This may be particularly important for the legitimacy of reinterpretation cases where views may start from more polarised positions. Prior to any project, it is important that decision makers take time to identify and engage the range of relevant stakeholder groups pertinent both to the heritage asset itself, and those with interest in the broader context of the contested history. The consultation stage can be used to test the narrative for the proposed project.

Where groups and individuals with a wide spectrum of different views are engaged with in a meaningful way and from an early stage, this can also strengthen the legitimacy for the reinterpretation work and build a broader consensus for the aims and intentions of the work. For example, the Reconciliation Reredos case study at St Stephen’s Church was able to secure wide support from church stakeholders and the public in Bristol, despite tense disputes in the city over contested history.

A well organised process of consultation will not dissolve different perspectives on history; but the legitimacy gained by conducting this process in a way that builds trust can mitigate polarisation, and build a broader consensus, or create new opportunities for more constructive dialogue and engagement by those with different views.

Steps that can support effective consultation

- It is useful for a consultation process to be structured by a clear and published set of principles, which can help to secure trust from those with potentially different views on interpretation of the history.

- Those leading the reinterpretation should reach out to and seek input from a broad array of different stakeholders. Provided their views are not hateful or discriminatory, all interested parties should feel able to contribute.

- Internal stakeholders with associations to the site or organisation should feel their views are valued and represented.

- Members of the public and the local community should have opportunities to contribute and share their views.

- Most importantly, the voices of those impacted by or connected to the relevant contested history should be heard and represented in the consultation. This may require contacting people directly connected to or descended from those involved in the history which is being contested, particularly where reinterpretation involves forms of commemoration. In certain contexts, for example pertaining to colonialism or transatlantic slavery, or other forms of historic discrimination, the process should also engage local residents or community groups from specific ethnic, faith or social groups, nationalities, gender identities, or sexualities.

- For smaller projects, there will be challenges of resources and capacity, knowledge, networks and confidence to do this. This would make tailored advice on how to act in this spirit with limited resources, and the identification of potential points of advice and support in doing so, more important.

Recording public feedback

Measuring and, where possible, systematically recording public feedback to reinterpretation work was an element of the process sometimes neglected within the case studies examined. Responses to the projects were often gauged anecdotally. This may tend to capture the views of the most vocal, which may or may not be a useful guide to the broader range of public responses.

Reinterpretation should not always be seen as a one-off event. Rather, it may be considered part of an ongoing process, where new layers of reinterpretation are added over time to reflect changing evidence, new levels of public interest, or shifting social values.

From simple approaches, such as the visitor book kept in St Mary’s Church, to more empirical survey studies, for example in the evaluation held on the Liberty and Lottery exhibition at Brodsworth Hall, feedback systems are important to ensure that reinterpretation is impactful and communicable. Logging public responses is moreover necessary to mitigate risks of offending or misrepresenting some audiences, to give an opportunity to respond to feedback and adapt the approach if needed, and to limit the potential for incurring controversy as broader public debates over contested history evolve over time.