Research fills in the gaps left by previous generations' recording of history revealing a host of fascinating and inspirational stories.

Uses and Abuses of Property

For those women in the 1850s who wanted to get involved in the political process to change women's lives there was no question of them attending public meetings. It simply wasn't considered appropriate. As such, they had to find alternative options.

As the suffragist Ray Strachey (1887-1940) later wrote, 'the very existence of a committee of women was a startling novelty'. For some women with liberal parents, often non-Conformist or Quaker, the home was the alternative venue for political meetings. Barbara Leigh Smith (later Bodichon) (1827-1891) had a liberal education at her childhood home at 9 Pelham Crescent, Hastings, and later used her home at 5 Blandford Square, London NW1 politically as a campaigning centre.

In 1855 the Married Women's Rights committee, based there, co-ordinated the 70 nationwide petitions totalling 26,000 signatures, including those of Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861), and Elizabeth Gaskell (1810-1865). Mrs Gaskell was then living at 84 Plymouth Grove in Manchester, another centre for women's activism.

Areas of London with concentrations of activity became recognised as hot spots for women's rights. Kensington was one such place with the Kensington Society (1865) which campaigned for education, property and suffrage rights named after its location. The meetings were held at the home of Charlotte Manning (1803-1871), 44 Phillimore Gardens, Kensington, London W8.

The Society presented a 1,499-signature suffrage petition to Parliament on 7 June 1866. This was the first step towards votes for women.

A year later, at the mid-18th century home of the abolitionist and early suffragist, Mrs Clementia Taylor (1810-1908), Aubrey House, Aubrey Road, Kensington, London W8, women involved in the suffrage petition were present at the meeting of the London Society for Obtaining Political Rights for Women. It then changed its name two weeks later to the London National Society for Women's Suffrage.

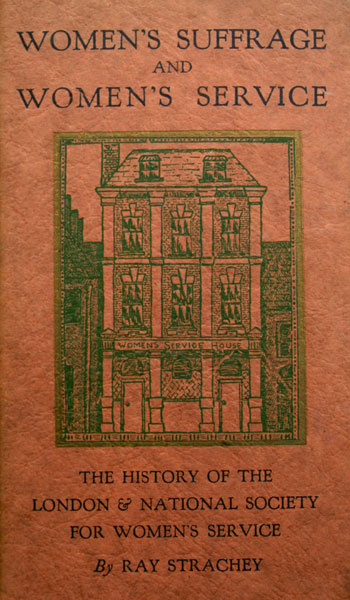

Moving from this private home to a series of rented offices, after many name changes, the London and National Society for Women's Service bought its first property with a £1,000 anonymous donation to the leader of the non-militant suffragists, Millicent Fawcett (1847-1929). In 1926 the Fleece Inn at 35-37 Marsham Street, Westminster, London SW1 was converted and renamed the Women's Service House. Alterations provided the perfect headquarters with a well-stocked library.

By 1929 they had planned and commissioned a new building with conference hall, library and restaurant, the Millicent Fawcett Hall, 31 Marsham Street, Westminster, London SW1. Many moves later, those very books are housed in the Fawcett Library's 2002 reincarnation, The Women's Library, London Metropolitan University, Old Castle Street, London E1 created by architects, Clare and Sandy Wright.

At the end of 1911, after further rejection of their claims by Prime Minister Asquith, the suffragettes escalated their militant tactics against property.

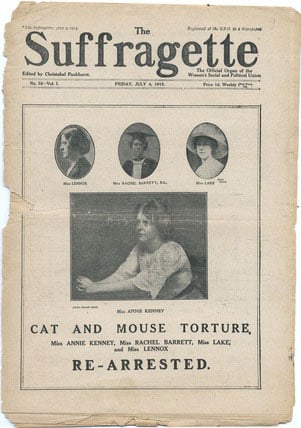

By 1913 the suffragettes had undermined women's seclusion in respectable middle-class homes by using them as 'safe houses' to escape the police. Imprisoned hunger-striking suffragettes were potential martyrs to the Cause so the Government passed the Prisoners' (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act releasing suffragettes to recover their health before re-arresting them.

The police's problem however was finding them again, hence the nickname, the 'Cat and Mouse Act'. The home of Mrs Hilda Brackenbury, (1832-1918), at 2 Campden Hill Square, Kensington, London W8 became famous as 'Mouse Castle', while Elizabeth Robins' (1862-1952) Sussex farmhouse, Backsettown, Henfield was for 'country mice'.

Visible in Stone - Uses and Abuses of Property

Please click on the gallery images to enlarge.