The history of people with disabilities since 1050.

The Right to Education - the Growth of the 'Special' School for Children with Disabilities

In this section we explore how children with disabilities gained the right to education in the early 20th century. For some it was progressive and highly innovative, but for others, it could be a brutal experience.

In this section

Audio version: 🔊 Listen to this page and others in 'Disability in the Early 20th century' as an MP3

The move towards special education

Local authorities had been responsible for educating blind and deaf children since 1893.

The 1918 Education Act, made schooling for all disabled children compulsory. It was a very significant piece of legislation. By 1921, there were more than 300 institutions for blind, deaf, 'crippled', tubercular and epileptic children.

It was often thought that children with disabilities were better off away from their families, so even though a small number of them stayed in mainstream education, many left home to go off to residential schools.

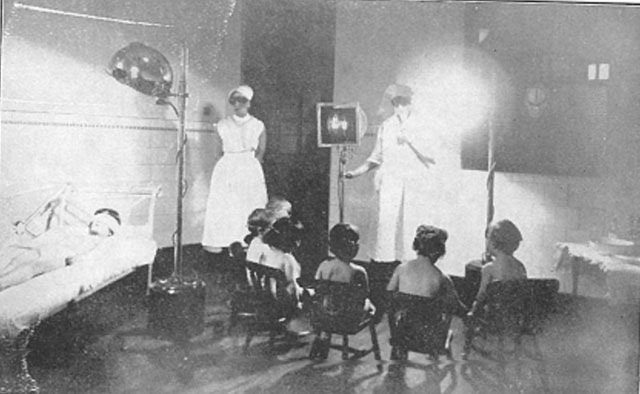

Improvements in children's health

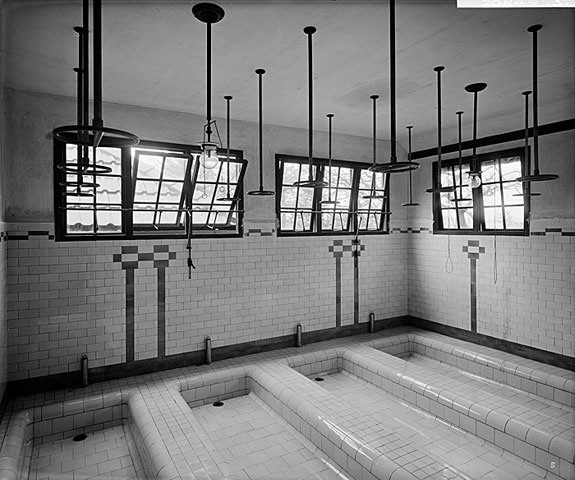

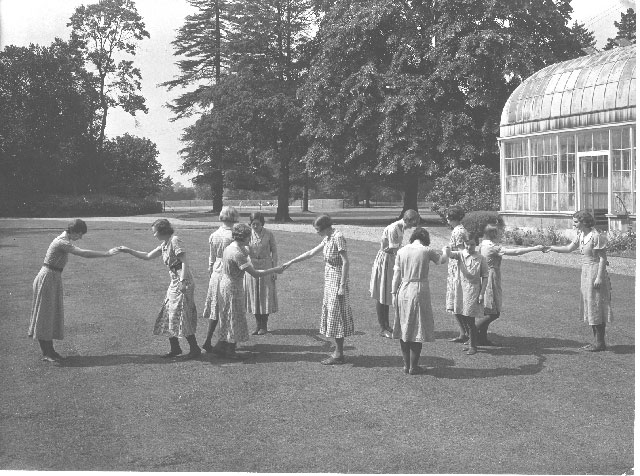

From Germany, the idea of the 'open-air school' came to England. Sick or disabled children studied in outdoor classrooms. Their diet was improved. Even in winter, wrapped in blankets, they took their afternoon naps outside.

The first of these schools was opened in 1907 by London County Council at Bostall Woods, Woolwich. By 1939 there were 150 open-air schools, providing places for almost 20,000 children and here, away from unhealthy, crowded home environments, their health began to improve.

Progressive and innovative schools

The Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) set up a network of 'Sunshine Homes' which pioneered liberal and progressive teaching and care methods. The first was opened in 1918 in Chorleywood, Hertfordshire, with an intake of 25 blind infants.

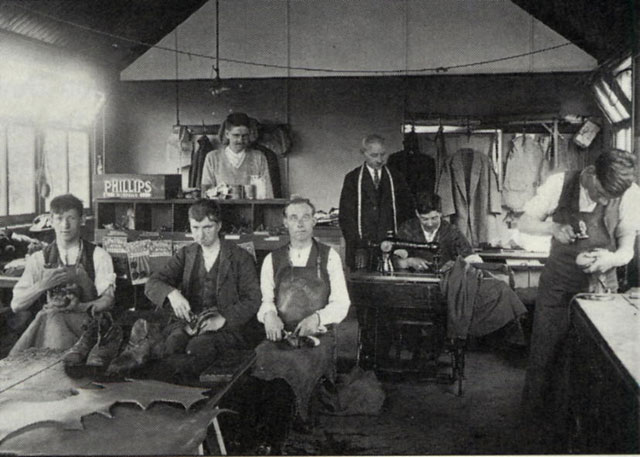

The Chailey Heritage Craft School in East Sussex was founded in 1903 under the banner of the 'Guild of the Brave Poor Things', a self-help group for young disabled people. The school took in disabled children from deprived city areas and taught them crafts in a countryside setting, with the aim of helping them become independent adults.

Harsh disciplinarian regimes

Although the right to education was a great step forward for disabled children, in practice it was sometimes a mixed blessing.

There was often a focus on low-skilled work training rather than full education, and many educational regimes could be harsh and highly disciplinarian. Parental visits were discouraged and letters home were censored.

In 1915, a group of blind boys made a night-time 'escape' from the Mount School for the Blind and Deaf in Stoke on Trent, Staffordshire. They wanted to contribute to the war effort by working on a farm but they were caught. Back at school, they were forced to hand in their trousers each night to stop them escaping again. They were also placed with the deaf children as a punishment; the blind children couldn't see, and the deaf children couldn't hear, so they struggled to communicate.

A combative atmosphere

Such harshness often led to aggressive attitudes between staff and pupils. Pupils at the Manchester Road School for the Blind in Sheffield, South Yorkshire went on a two-day strike after a pupil was severely disciplined for something he had not done.

Although deaf children preferred to sign they were often required to learn to lip-read. At the Yorkshire Residential Institute for the Deaf in Doncaster, pupils used sign language in secret so they could retain some independence.

The sexes were always rigorously separated, but boys and girls still found ways to communicate with each other. We know, for example, that pupils from the Halliwick Home for Crippled Girls in Edmonton, North London would often slip crumpled notes to the choirboys on their weekly visits to church.

Watch the BSL video on the growth of the 'special' school for children with disabilities

The Right to Education

Please click on the gallery images to enlarge.