Join us as we travel across England visiting well-known wonders and some lesser-known places on your doorstep - all of which have helped make this country what it is today.

100 Places Podcast #35: Chatsworth and Kelmscott

This is a transcript of episode 35 of our podcast series A History of England in 100 Places. Join Dr Suzannah Lipscomb, Will Gompertz, Duncan Wilson, Deyan Sudjic and Nia Evans as we continue our journey through the history of art, architecture & sculpture in England.

A History of England in 100 Places is sponsored by Ecclesiastical

Voiceover:

This is a Historic England podcast sponsored by Ecclesiastical Insurance Group.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Hello, I'm Dr Suzannah Lipscomb from the University of Roehampton. And you're listening to Irreplaceable: A History of England in 100 Places.

In this series we explore the amazing places that together tell the story of England. Ten expert judges have worked across ten categories and thousands of your nominations to compile a list of 100 places, which have helped make England the country it is today.

If you're enjoying the series, don't forget to subscribe so you don't miss an episode. And if you're listening on iTunes, please rate this podcast and leave a review.

In this episode we are continuing our journey through the Art, Architecture & Sculpture category, which has been chosen by Judge, BBC Arts Editor, Will Gompertz.

Joining me in the studio to discuss them are my guests, Deyan Sudjic, the Director of the Design Museum, and Duncan Wilson, Chief Executive of Historic England.

We begin today's episode with our sixth location, the magnificent Chatsworth House in Derbyshire. Chatsworth has been labelled, 'the palace of the peaks' and features more than 30 rooms, a vast library and a truly magnificent art collection.

There is also the 105-acre garden, a beautiful site in summer, and a public park on the banks of the River Derwent. So why did Will Gompertz choose Chatsworth house?

Will Gompertz:

I mean in any list of British buildings which sort of sum up the country, you have got to have the great English stately home. For me the greatest of them all is Chatsworth house in Derbyshire. It's just such a phenomenally beautiful building, which has kind of been added on and rebuilt over time, but it still maintains this wonderful, Georgian stature in the landscape. It sits in the rolling hills of Derbyshire, in the landscape. And it does so almost with such ease as if it's always been there, as if it's an ancient rock which belongs there, that's come from the earth and come from the ground. The stone is so beautiful. The shape of the building is wonderful. The way it sits in the valley is beautiful as well.

And of course the gardens are great. Then you go inside Chatsworth and the current Duke has maintained an interest in art, which you can see when you walk around the building- that he's got wonderful contemporary artworks, which are married against and with, older artworks from previous centuries.

The whole thing just feels like it's alive. Often with these old country houses, you can feel they kind of died a long time ago and they're just being kept open as historical monuments, but not Chatsworth. Chatsworth is something that continues to be alive, continues to be vital, continues to be a wonderful, significant space and place in the English landscape.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

It's not hard to see why Chatsworth has been chosen. But let's hear more from the 'palace of the peaks'.

Nia Evans:

My name is Nia Evans. I'm both a house guide and I also work in the collections department, currently as the archives and library assistant.

Chatsworth is one of the most prominent houses in the middle of Derbyshire. It all goes back to the middle of the 16th century, when a very important lady called Bess of Hardwick, with her second husband, bought the land in 1549.

We are now on our 16th generation of that same family.

At the time the fourth Earl, who became the first Duke of Devonshire, had a very European taste. The house that was here at the time was a really typical Tudor style house. So that was built by Bess in about 1549, 1550. At this time the family wealth had really started to grow and the Tudor style house wasn't quite befitting. It wasn't very smooth…it was a bit sort of clumsy. So what he did, he travelled a lot in Europe and he wanted to base his new house which would befit his new status as a peer in the land, on this very forward-thinking, very modern style. It's basically a French hunting château, they think based on the Château Marlow, which was a hunting château from Louis XIV's time.

In the late 1700s, they removed hills, entire hills to basically open the landscape up so you really got the scene of the house as you came in. They rearranged the river at one point! A very famous landscape gardener, Lancelot Capability Brown, he actually straightened and widened it so the approach was even more impressive.

So these small details which we now see, we might not even notice, are really man-made and they've been really thought about.

Because the family has been here for such a long time, they have amazing pieces by the likes of Rembrandt, by Van Dyke, by Raphael. Artists which are really well known.

One of the things that makes this collection so special is that every generation of Duke always hired contemporary artists. So as you walk round the house you see modern ceramics, you see things which, you know, have only just been brought in.

It constantly keeps us on our toes and constantly keeps the visitors, who might come to Chatsworth expecting to see an old house with these beautiful statues in. But they'll come in and see a digital portrait, which is changing colour, ceramics which are these bright colours, and the fact that it is all intermingled is trying to open people's eyes to actually how inclusive it all is.

This is what we call the, 'Painter Tour', and this would have been the main reception hall of the house. So really spectacular.

[Bells ring].

The bells that you are currently hearing, they are part of an art installation that we have in the house for this year. Linder Sterling lived on the estate for about nine or ten months, something like that- she wanted to live and breathe Chatsworth and come up with an installation specific to here.

The bells you are hearing are part of that installation, but within this we also have a beautiful incense burner going for this year and we also have these really dramatic capes on the balconies that you can see.

So every generation of family has added something in some respect. They're basically continuing it for the next generation because if the family stopped buying pieces in to the collection, then suddenly the house would stop being modern, stop moving along with everyone else.

So I've brought you into the garden. You've got an amazing view of the house on one side, but on the other side we have one of the earliest water features, that we had, The Cascade.

Now this is all done by the first Duke. This is actually the second one that was built here. The first one was done about 1696. Four years later, the first Duke realised it wasn't quite impressive enough for him, so he had it taken up and replaced with this one, which was that bit longer into the garden, and he thought had more of a "wow" effect to it.

What I love about Chatsworth is that you will get people of all different backgrounds. The artwork is constantly evolving- it's not just about paintings. Some of them are beautiful and there is so much linked to science and architecture. It's really showing where art can take you.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

That was Nia Evans from Chatsworth House.

As we have heard, the house truly straddles the centuries when it comes to art, architecture, and sculpture. I know how Chatsworth began: the estate was bought by Sir William Cavendish, the second husband to Bess of Hardwick, but it was really the extraordinary Bess who ran the project.

Her next husband after Sir William's death, was also called Sir William, affectionately nicknamed her, "my honest sweet Chatsworth" and the "chief overseer of the works", but what happened next?

Duncan Wilson:

The great Elizabethan building was re-modelled, rebuilt in effect by William Talman, who created a really extraordinary building in the English baroque style on the Elizabethan footprint. The baroque is all about theatricality, scale, drama and Chatsworth certainly in its setting delivers that.

Deyan Sudjic:

It is a very powerful composition in its landscape setting, but the interior is magnificent. It is room after room, sequence after sequence of extraordinary spaces.

And now what's actually so special about it is that it keeps that sense of being a living place. Generations of Devonshires have actually gone on commissioning serious new art. They've gone on actually keeping the place alive. It's got a sense of sincerity and authenticity about it and that's really special.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Yes, there is so much to see at Chatsworth. One of the things that's very clever is you can see the inner workings of the house through these cleverly placed glass panels- as you walk through you can see what's going on under the floor boards. But of course, as we are alluding to, the defining moment of Chatsworth in the 20th century was opening the estate to the public by the 11th Duke and Duchess of Devonshire. And the fact that it's still their home and they play this key roll in shaping the art collection both within and outside the house, is of course what it is known for.

It contains works of art that span 4000 years. They've got ancient Roman and Egyptian sculpture. They've got Rembrandts, and Reynolds, and Varanasis and of course work by outstanding modern artists including Lucian Freud. And the current exhibition by Linder Sterling brings us right up to date with her famous collages.

Do you think it's difficult to strike a balance between presenting ancient and modern art?

Deyan Sudjic:

So many of those aristocratic collections stopped around 1820 and what's so impressive about the Devonshires is they've gone on getting extraordinarily current work and they don't go shopping for fashionable artists names, but they do actually engage with them.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

If we think beyond the Devonshires, how important is Chatsworth itself in the local community and in England as a nation, I suppose?

Duncan Wilson:

It employs lots of the local community. I think 700 was the figure I had, on everything from grounds maintenance to stone repair and cleaning and visitor management and all those things. So it's a major factor in the local economy, as country houses always were from when they were built onwards.

Deyan Sudjic:

But to successfully run such an enterprise is no easy feat. There's no sense of this as a bottomless pit of aristocratic wealth keeping it going, or gigantic government grants. It's not like that. It's a very entrepreneurial generation of the family who actually have built this up from a period when things were looking quite bleak in the late 50s and now it does have that sense of energy. It's actually transformed the area as well- there is a lot of investment because of them being there.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

These days, of course, there's a real appetite because of things like Downton Abbey! People want to go to these places and find out what the real story is. Actually, once you've got them in the doors it's extraordinary what you can then do- what you can then show them.

Deyan Sudjic:

There is that sense that to encourage people to go and look at the heritage in that sense you need to keep on redefining it and reshaping it and giving it a modern voice.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Chatsworth really is an irreplaceable location and one of the sites in our top ten which encapsulates art, architecture, and sculpture.

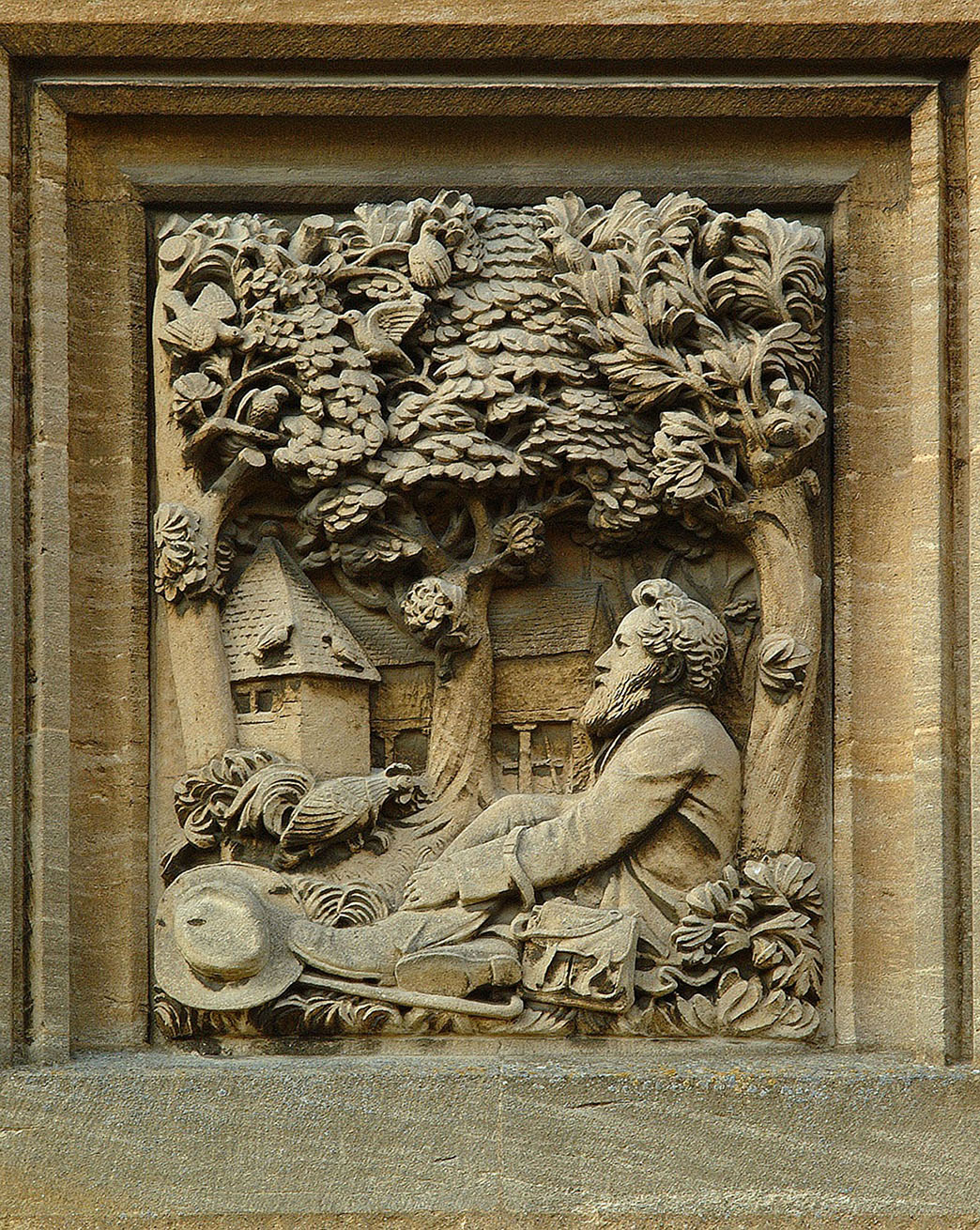

But now we move away from Derbyshire to our next influential home. Kelmscott Manor in Gloucestershire is the Grade I listed farmhouse and summer home of William Morris.

Now, we've come across a William Morris earlier in the series when we were talking about British car manufacturing, but this is another William Morris. The English textile designer, poet, novelist, and founder of the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings, or SPAB.

He is most closely associated with the Arts and Crafts movement, which flourished in late 19th century Britain. Morris' home Kelmscott Manor was built around 1600 and lies adjacent to the River Thames at Lechlade.

Morris considered it to be so natural in its setting as to be almost organic and he loved its beauty. Why did Will choose Kelmscott Manor in his list of top ten nominations?

Will Gompertz:

The reason I love Kelmscott Manor is because William Morris loved Kelmscott Manor and I love William Morris. He was such a significant figure in the late 19th century and what Britain was doing and responding, and how we as a country were dealing with the Industrial Revolution. There were many great worries about it- this notion of the livelihood of men was being eroded and taken over by a mechanised age, which was brutal to man and didn't care for craft or individuality at all and just turned man in to a machine and this is what was happening. There you have William Morris trying to respond to that with the Arts and Crafts movement. So we have this great boom of industrialisation where man is treated like a piece of kit and Morris is saying, no, no, no, that's not right thing to do at all! You can have industrialisation but you can also add man's creativity to it. You can still make things beautiful. They don't have to become these great lumps of steel and stone; they can be carved, and turned, and made into something magnificent.

Morris was a visionary who believed in the materials of nature. He called it, 'a truth to nature', going into nature, finding the truth of nature, dragging it back into the industrialised world, and making these really beautiful objects. And in a way Kelmscott Manor exemplifies and encapsulates all that vision, because when you go round it, it's just made with these most beautiful materials. Inside there are lovely oaks, there is fantastic stone outside, fantastic tiles, and it's just made on a human scale.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

The house contains an outstanding collection of the possessions and works of Morris, his family and his Arts and Crafts associates, including furniture, original textiles, pictures, carpets, ceramics and metal works. What makes it so impressive do you think?

Deyan Sudjic:

There are really two William Morris', never mind the carmaker. There is William Morris, the designer of exquisite wallpaper still loved by the English Waitrose-buying classes.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

(laughs) I object! I have this at home.

Deyan Sudjic:

And there's the revolutionary socialist, feminist who devoted the later parts of his career to overthrowing the status quo in this country.

On one level you could see as being a completely irreconcilable confrontation. Morris believed in the dignity of labour and the joys of hand making and rejected machine-made work. He was memorably taken to, the Great Exhibition, in 1851 by his mother as a birthday treat and he refused to go inside on the basis that everything in it would be machine-made and meretricious. And yet when he set up his carpet-making workshop in Wandsworth, he used child labour because they had more delicate fingers. A very complicated mix.

Kelmscott is of course a beautiful house, which one would want to live in if one had the choice. Exquisite. The sense of all that was best about the past of England that Morris loved so much.

But he also used it as one of the settings for his novel, 'News From Nowhere', which was an anarchist manifesto which painted a picture of London after the revolution in which Parliament Square was a dung heap in which worthless banknotes fluttered in the air…

Suzannah Lipscomb:

What a lovely picture! What do we know about Morris' life at Kelmscott?

Duncan Wilson:

Well, it was complicated and exotic, in a sense! He moved there with Rossetti, who was in love with the Morris's wife, who featured in many of Rossetti's famous paintings. And Morris was clearly semi-tolerant of this relationship and kept disappearing to Iceland when I think the atmosphere got too frenzied. But he was not happy about it. In the end it moved on and Morris and his wife stayed in Kelmscott. But I think that is a really important part of the story of Kelmscott and Morris' life.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

In fact we have accounts of Morris saying that Rossetti had "set himself down at Kelmscott as if he never meant to go away". Quotes like that give the impression that he loved the place and was rather more perturbed about Rossetti taking the house than the wife! How do you think that impact of Rossetti on William Morris and Kelmscott, how do we see that really?

Deyan Sudjic:

You could say this house represented a retreat. Morris' great contribution was to set up Morris & Co in Bloomsbury, which started to make furniture and to make wallpaper. It was a business, and you could say this was a retreat into another kind of life.

Duncan Wilson:

It's easy to view Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement as something that kind of happened in a bubble, but actually there are so many resonances of what he stood for today. I mean, I was thinking about in terms of food- the organic food movement, about what is real and what is of the soil and what is not industrialised and processed. And actually that's what Morris stood for in his attitudes towards manufacturing and decorative arts. So I think there is a lot to learn from him.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

There is an extraordinary legacy and influence from Morris' Arts and Crafts movement, the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings, which really changes people's minds about how you should approach the restoration of the past doesn't it. And in that we still see his legacy living on?

Deyan Sudjic:

Yes, I think SPAB, as it was called affectionately, was behind the anti-scrape movement. It was saying that you restore buildings not by making them look like they once were but to patch them to show where new things have been inserted to actually reflect on the passing of time. It's kind of anti-Botox conservation.

Duncan Wilson:

That too is a very current debate. We may feel we have adopted the principles of SPAB in England but actually I'm not sure we have. Even if we have there are plenty of places where we are engaging in dialogue about conservation and the SPAB principals seems to be quite new.

Suzannah Lipscomb:

Quite the legacy from just one man.

Well, that's all for this episode. Thanks again to my guests Deyan Sudjic and Duncan Wilson and of course, Will Gompertz, our Judge for this category.

We've got three more Art, Architecture & Sculpture locations to reveal next time, so join us all then. And don't forget to subscribe to this show on your podcast app.

You can join the conversation by using the hashtag 100 places, and find out more online at HistoricEngland.org.uk/100 places.

I'm Suzannah Lipscomb. Many thanks for listening.

Voiceover:

This is a Historic England podcast sponsored by Ecclesiastical Insurance Group. When it feels irreplaceable, trust Ecclesiastical.